|

Let’s get straight down to it. What’s a spy story? And then what’s ‘spy adjacent’? The latter is a term I’ve encountered in the always thought-provoking Spybrary facebook group, most recently in a debate about whether The Third Man is a spy story or not. As I said, thought-provoking. Let’s start another way... What is a spy? When I was a kid playing my Waddingtons board game Spy Ring, I thought it was obvious. A spy was someone in a hat and trench coat, collar turned up, lurking around near embassies (whatever they were) who felt a bit like the cartoon detective in The Pink Panther (some confusion creeping in there)… …and what he wasn’t was a secret agent, who was someone who wore slick suits, used gadgets and drove cars that you could get Corgi models of – not only Bond’s DB5 but even The Man From Uncle’s ‘THRUSH-BUSTER’!! (Google it. Carefully.) At which stage, if you’re like me, a couple of things probably happen next. Maybe you’re caught spying on your sister or a neighbour sunbathing. Now you know what spying means – and the importance of avoiding counter-espionage measures. Or, some smart-arse mocks you for getting MI5 and MI6 mixed up and you vow never to make the same mistake again, even if virtually everyone else does… I mean seriously, it’s like apostrophes! Eventually, of course, you read le Carré and the like and you come to accept that an agent or a spy isn’t what you thought; that’s an agent runner or a case officer. Or maybe they’re assets handled by intelligence officers. And along the way you learn the difference between legals and illegals, espionage and counter espionage, and counter intelligence and… well, maybe that’s still a little confusing. Especially when you read Spycatcher and realise how much spying goes into countering it. Or anything about all the WWII agents being turned and run back as doubles. The big takeaway, of course, as childhood absolutes start acquiring shades of grey, is that a spy is probably not a highly-trained, bikini-babe-bestrewn action hero and more likely someone who’s been manipulated into betraying secrets by an equally morally compromised handler. At least, that’s what the prevailing wind in fiction has been telling us ever since le Carré and Len Deighton punctured Fleming fever and reminded us about Graham Greene. Which brings me back to The Third Man, for which Greene wrote the screenplay, and to that cursed term ‘spy adjacent’. What does it mean? On the face of it, it appears to signify a story which, whilst brushing past the world of spies and spying, is really focused on something else. Black Ops maybe. Or a love story. Or, as with The Third Man, crime. But, I think, that word ‘Crime’ exemplifies the problem, especially with a capital letter. This isn’t really about understanding and redefining works of fiction for the purposes of literary or media studies. It’s about shoving them into genres for the sake of convenience. If it’s structured like a detective story, with a murder, an investigation, a revelation, a capture – and/or if it's rooted in the world of organised crime (both of which are true here) – it’s a crime story. And if it’s on film, especially shadowy black & white with lots of hats and Dutch angles, it’s Noir. So even if it feels like a spy story, sorry, it can’t be. It can only be ‘spy adjacent’. Which in this particular case is fine, I guess. I mean, I might argue that a story set in the Inter-Allied Zone in post-war Vienna, in a milieu that’s so stuffed with spies and secrets that the policing has to be done by MPs who seem a lot more like military intelligence or counterintelligence officers... a story which features an antagonist who’s doing unspecified favours for the Soviets in return for safe haven in their zone and has a Russian ‘liaison officer’ plotting to forcibly repatriate a Czech émigré and presumably falsely accuse her of espionage… still feels kinda spy-ish. Not least because what it’s really about is betrayal, and that’s as spy-central as it gets. But OK, the main thrust of the story is about racketeering not politics and the main character does more investigating than actual infiltrating. It’s spy adjacent. Got it. So what about The Odessa File and The Day of the Jackal? They’re political, and they feature operations to counter underground groups – the kind of thing MI5 and its pretty-spy-ish operatives would be getting involved in if they were set in Britain instead of France and Germany. Plus, with all their assumed identities, they feel like espionage thrillers, and one of them gave us a piece of tradecraft that is still shamelessly imitated to this day. Are they only spy adjacent too? Seemingly so. And seemingly, I would argue, because it’s an easy catch-all basket for anything which isn’t quite what you expect a spy story to be. But hang on a moment. Not every spy story has to feature spies acquiring state secrets or spy-catchers catching moles or Jackson Lamb letting out another fart, does it? And I’m not talking arty-farty genre-crossing either. I mean… Thunderball! By which I mean many other Bond stories too, of course, and much besides. SPECTRE doesn’t really seem to do much Counter-intelligence, Terrorism or Revenge when it comes down to it. It’s all about the Extortion. It’s a racket, like Harry Lime’s black market penicillin. So does that make it spy adjacent? Or take another example. The much-adored spy thriller The Night Manager. The antagonist is an arms dealer, a racketeer. And the protagonist, although recruited and prepped by the spooks in classic le Carré style, is a civilian who has blundered into this world and is motivated by personal feelings, just like The Third Man’s Holly Martins. So is this to be rebranded ‘spy adjacent’? OK, it has some Bond-esque ‘undercover’ behaviour and some Bond-esque locations to make it feel less like a crime or revenge thriller – but then, in the TV version, it also presents us with a glimpsed shopping list of the latest British weapons that puts it firmly in the realm of outright comedy (Vulcan bombers and Trident submarines for crowd control, I seem to recall…) The fact of the matter, surely, is that much of what we call spy stuff is more like the above. As the Cold War developed (or didn’t) and then ended (or didn’t), we tired of faceless KGB apparatchiks (erm, yeah...) and demanded a more varied cast of baddies, which of necessity brought in colourful criminals of all kinds – often linked to espionage, sometimes not, but rarely perceived as just being (ho-hum) adjacent. And I’m thinking, too, (because I usually do) of Modesty Blaise. She was frequently touted as ‘the female James Bond’ and referred to as a glamorous spy or secret agent, presumably because she was recruited by British Intelligence. But look at those jobs she was recruited for, or accidentally fell into in later stories. Almost invariably they involved drawing on her criminal background to take on some of that colourful cast of criminal baddies, and often by confronting rather than spying on them. Doesn’t that make her at best spy adjacent? Because I’m coming to the point at last. Modesty was a large part of the inspiration behind my ‘Chasing Mercury’ series, even though they’re set more in The Third Man’s milieu. I confidently decided that the first book, The Borodino Sacrifice, was a historical spy/action thriller. It features a rogue wartime secret agent and an ex-soldier recruited by British Intelligence to track her down in the ruins of post-war Europe, as the Iron Curtain descends with all the political intrigues that entails. The antagonists are renegade Nazis and several competing Soviet intelligence and counter-espionage agencies, including SMERSh. So spy, yes, not adjacent? Then the sequel, The Herrenhaus Forfeit, which launches at the end of August. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a continuation of the first book, as well as a standalone adventure in its own right. But for this novel I’ve changed things up. This time the main antagonists are either British gangsters who’ve infiltrated the occupation forces in Germany (there’s a big heist at the centre of the narrative) or nefarious shadow-state organisations smuggling weapons and refugees. So can I carry on calling it spy, or is it – despite the continued reliance on subterfuge, infiltration and cover stories – shuffling towards spy adjacency? See my point? And what’s really silly (and has prompted this outburst) is that while plotting the third book, The Safehaven Complex, I’m currently losing sleep about whether or not to nudge it back closer to pure-blood spy – at least partly in deference to the non-existent sanctity of non-existent divisional boundaries in a non-binding genre we all know is largely fictional anyway! Right. Better get on with it… THE BORODINO SACRIFICE is available on Amazon. I am seeking ARC readers for THE HERRENHAUS FORFEIT, so if you'd like a free copy (no obligation to review) get in touch.

0 Comments

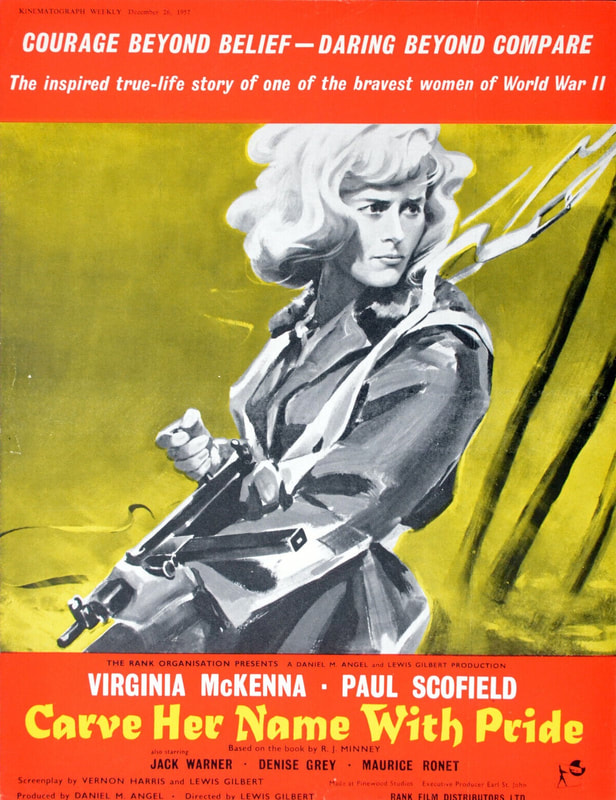

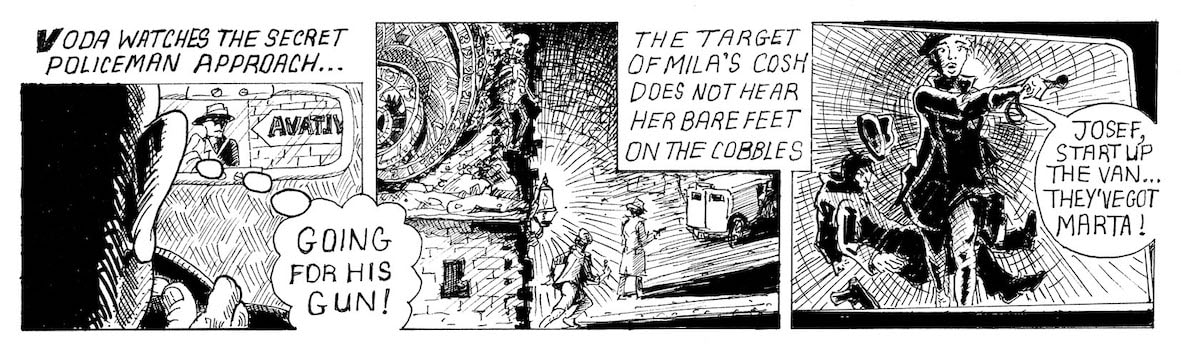

I touched on this (pardon the pun) in my post about getting iconic weapons wrong... Sometimes the difference between seeing something in a book/online and physically getting hold of it (or having a ride in it, or using it, or going to the actual location or whatever) isn't just the obvious sensory authenticity with which you can now layer your writing. Sometimes it's so surprising it sparks a whole fresh idea. Take the 2-Franc coin on the left, dated 1943. I just pulled it and its 1945 sister out of a childhood coin collection in an old cigar box in the garage – almost by chance but also because I was curious about the differing designs. You see, one was minted during the German occupation and the other after Liberation. In many ways, 1943 was the worst of times. By then, the Nazis had finally occupied all of France and the oppressive reality of that was even reflected in the coinage. In place of the personification of Liberty and the Republic, you got an axe, a couple of sheaves and FRENCH STATE. Instead of Equality and Fraternity... WORK, and FAMILY (as in 'you wouldn't want anything to happen to yours.'). Not to mention what the coins are made of – scrap aluminium. They weigh almost nothing. And that's what got me thinking. Idly, I tossed one – and failed to catch it. Whether because of muscle memory or a light breeze, I found it surprisingly hard to do, because of the coin's uncanny lack of mass. So imagine a Special Operations Executive agent sent to work with the French resistance, unfamiliar with the latest coinage. They have to decide between two targets to sabotage, they flip a coin and... I dunno. As I've said before, I don't write about F-Section; I let others do that. But it's either a nice little tactile detail or, potentially, some kind of initiating incident. And I wouldn't even have thought of it if I hadn't picked up the coin, that's my point. Anyway, you can have that. Maybe someone can do something with it. Vive la France! Imagine you’re a Czech dissident or anti-communist – or just a believer in democracy, or even just an intellectual. Maybe you fought on the “wrong” side during the war (still against the Nazis, but with the Czech army-in-exile in the west instead of the communist-sponsored partisans in the east). Or maybe you just have a big house with some nice things in it. The problem for you is that it’s February 1948 and the communists have seized control of Czechoslovakia in a coup d’état. You’re going to be on their list. You don’t know what to do. Then you’re introduced by a friend of a friend to a young woman who says she can help. Her name is Milena Markova, but maybe she calls herself Vanda Roubalova, or even (with encouraging resonances of old wartime resistance code-names) “Kolda”. She tells you she has contacts in the west, with the American intelligence services, and if you’re important enough, she might even confirm that yes, the dreaded Statni Bezpecnost or StB has its eye on you. So you liquidate your assets, gather together your loved ones, and arrange to meet her in the woods one night, near the German border. There you are passed to people smugglers or corrupt border guards who sneak you over a very convincing border to a US Army post, where you are welcomed by a member of the US Counter Intelligence Corps. And of course, during this interview, you are asked who told you about Milena Markova, and what other networks of dissatisfied Czechs you have heard about – after all, maybe you can help them escape too... You’re offered Lucky Strikes to smoke and American whisky to drink. Maybe you toast the portrait of President Truman that hangs on the wall. Then, having signed your statement, one of two things happens. Either you are sent on your own, carrying your signed confession, to another US Army post a little further through the darkened woods – and in this case, perhaps because you misunderstood the instructions and inadvertently wandered back across the border, you are caught red-handed by Czechoslovak border guards. Or, in the alternative scenario, the American officer’s welcoming manner hardens suddenly; he tells you that your application for asylum has been rejected and you are abruptly handed over to the Czech authorities (news of which perfidious western betrayal will filter back to the dissident underground on prison grapevines). Either way, you are arrested, stripped of your cash and valuables, put on trial and sentenced to hard labour or death, with your friends, family and helpers soon to follow. You’ve been caught by an entrapment “combination” run by the Czechoslovak StB (State Security) named Operation KAMEN or “Border Stone”. As Igor Lukes puts it in the CIA’s Studies in Intelligence (Volume 55, No.1), this was “a fiendishly clever scheme” involving false borders and border posts positioned well inside the actual border, fake German and American officers, and of course a network of agents provocateurs like Milena Markova. It was set in place as soon as the communists took power and continued running until the Americans, having learned the truth and issued formal protests that were mockingly dismissed, broadcast a public warning about the scheme on Radio Free Europe in 1951. As with many spy stories, it’s easy to sympathise with the poor victims, yet still tempting to romanticise other aspects of the operation, and none more so than the role of the glamorous femme fatale. But let’s look at her. According to one of the officers involved in Operation Border Stone, Milena Markova was no willing participant. She had been blackmailed into working for the StB because of her dishonourable behaviour during the war, presumably dating Nazi occupiers; and eventually, having been used too many times to continue as an effective decoy duck, she was herself arrested and held in solitary confinement, where she committed suicide. And that’s the point. At its heart, or in place of its heart, this “fiendish scheme” is another brutish tale. The StB were operating far beyond the law, sometimes gunning down escapers to satisfy personal grievances, always robbing them of their valuables along the way – and even targeting people not for ideological reasons but purely for the likely profit to be made. Which, I think, is why we want spy fiction, in place of spy fact. Because even when we congratulate ourselves on preferring the supposedly de-romanticised stories, deep down we know we still like them fictionalised and dramatized. The alternative is too damn ugly. Nor does it take much to imagine how versions of this scheme are being played out today. I am indebted to the aforementioned piece “Ensnaring the Unwitting in Czechoslovakia – KAMEN: A Cold War Dangle Operation with an American Dimension, 1948–52” in Studies in Intelligence Vol. 55, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2011), as well as to the article “Refugee trap at the wrong border” by Tabea Rossol in Der Spiegel (November 1, 2013). The image depicts an actual StB agent, disguised as an American, interviewing the Czechoslovakian Jaroslav Hakr. (Photo: abscr.cz Archiv bezpecnostnich sluzeb, ABS H-253.) My (very fictionalised) spy story The Borodino Sacrifice is available now on Amazon: mybook.to/Borodino Launch day is upon us! (For the eBook anyway – thanks to my amazing forward-planning abilities, the paperback is following in a couple of days, on the 3rd of this month – oops!) The early reviews have been really encouraging (thank you all!) but I left it so late that I urgently need more of them if I'm going to stand a chance of standing out at all... So, please, check out your local Amazon page for THE BORODINO SACRIFICE at mybook.to/Borodino – and also sign up for the Chasing Mercury News & Stuff substack – come find me on X @paulphillips44 – and share, share, share! Here's Virginia McKenna as Special Operations Executive agent Violette Szabo, in that stiff-upper-lip classic Carve Her Name With Pride (a movie on which, as I've already mentioned, my Uncle John assisted in an uncredited capacity, alongside SOE's mysterious Vera Atkins and a couple of her surviving field agents).

The scene with poor injured Violette holding off the whole Das Reich Division was an inspiration to me from a young age, as it obviously was for the illustrators of the poster – and no, in the movie itself, as in real life, she didn't still have her parachute harness attached! But what she did have, as you can see, was a Sten gun: the iconic epitome of Britain's unglamorous, utilitarian, egalitarian war effort. (Yes, I'm back on that again...) Cut to the present. I'm reading a newish novel set in the world of the F-Section agents and thinking it a pretty good twist on a familiar subject, actually. But one thing keeps jarring – the description of the Sten gun as an American weapon. I know. Yawn. Mansplaining bore nit-picks on something no one else will notice. But in fact, since I can’t remember which book it was and I had two on the go at the time, one by a female author and one by a male author, it may not technically be mansplaining at all. And if I am indeed, briefly, nit-picking, that’s not my purpose here. You see, I am British, with a dash of South African and German, so obviously I wouldn’t want the ‘ruddy Yanks’ to get credit for the cheap-and-dirty submachine gun we bashed out for troops and resistance fighters alike during the war (nor, I gather, would they want it). Also, being British, I dread the embarrassment of being seen to get something wrong – or even the embarrassment of just imagining the embarrassment of being seen. But as I might have mentioned, I am British (more or less) and as such I don't have the option to teach myself by shooting off military weapons at the range. Air rifles and shotguns, that’s our limit here (although my South African roots have enabled me to get shot at by more exotic firearms, so there is that…) So no, I'm not pontificating. What this is is an expression of sympathy with authors of action sequences who can’t quite get their heads around the weapons involved – for I am one of you! Here’s an example. When I wrote my early drafts of The Borodino Sacrifice, in which my male MC snatches a Sten away from my female MC in Chapter One, I had her bring the gun to bear on him and him think thus: …there should have been a side-loading magazine and it looked like this one had come off in the crash. (He) didn’t think she’d be fool enough to drive around with the gun cocked: these knocked-out British weapons had no safeties to speak of. Sounds OK, right (if a bit derivative maybe)? Establishes his proficiency with all things military (we’ve only just met him, after all) and makes me sound like I really know my stuff. Except I don’t. Because the thing I’d picked up from the likes of the Bond books and was trying to get across – that guns can still have a round in the chamber, even if the magazine is out – applies to certain guns, like 007’s semi-automatic pistols, but not to simple blowback submachine guns like the Sten. And, thankfully, I doubted myself enough to check. A-ha! Wikipedia told me that the Sten 'fires from an open bolt'. But what did that even mean? I couldn’t get my head around it. We may have played WWII soldiers with Tommy-guns as kids – as I riffed off in my still-to-be-completed novella 76 – but none of those gloomy neighbours who’d done it for real stopped and showed us how they worked, and nor did any of the war films, not really. So I had to dig deeper, and I discovered the world of YouTube firearms content, which includes all the wannabe Navy Seals, as you can imagine, but also a few responsible channels run by dedicated history and engineering experts. From whom I found out about guns like these: how unlike ‘closed bolt’ firearms that are cocked and locked with the bolt forward and a round in the chamber, when you cock the Sten by pulling back the bolt like Virginia here and then you pull the trigger, the bolt comes forward, strips a fresh round out of the magazine, slams it into the breech and fires it all in one go (and so on, and on). So the finished draft just has to say: …but its distinctive side-loading magazine was missing. He snatched it from her. …which unfortunately doesn’t make it sound like he or I know anything clever about the weapon, but is more accurate and plausible than what I had before. (And shorter. Hooray!) From then on, there was no stopping me correcting myself. Mercifully, writing about the immediate postwar period, I didn’t need to describe any characters thumbing back the hammer on a Glock or clicking off its safety catch (neither of which it has), but I was able to steer clear of other notorious pitfalls such as the ‘smell of cordite’ (keep that for my Boer War period epic…) or a revolver with a silencer… And that’s really all I wanted. To avoid making a fool of myself. Not to give characters who've just picked up a gun an unlikely knowledge of that gun, and definitely not to info-dump gun porn on the reader by having a character think that an MG-34 is firing 7.92×57mm Mauser... but rather to get it right that in this period he’d probably (and wrongly) identify the machine gun as a ‘Spandau’ and not an MG-34 at all. But here’s the thing. Along the way, I started caring about the more egregious errors I encountered, because they reflected how a lack of knowledge (or an acceptance of TV cliches) can influence your narrative detrimentally. An example would be the habit of interchanging rifles and submachine guns based purely on the coolness factor, without stopping to think that one is designed to hit something far away, sometimes even further away than you can see with the naked eye, and the other’s basically for pistol range only – Lost and Walking Dead fans take note! In a similar vein, on a subject I know even less about, I've heard that archers get furious with Legolas et al for drawing their bows and then keeping them drawn to threaten people or make long speeches, as though they were handguns and not weapons based on completely different and very physically demanding physics… Plus I started seeing how choosing to feature more appropriate, interesting or, yes, forgotten weapons instead of the obvious ones had the potential to enrich the story – in exactly the same way as one might avoid overworked settings or character traits to make them more distinctive. So by the time I got on to Book Two, I was letting Ian McCollum of Forgotten Weapons and Jonathan Ferguson from the Royal Armouries point me towards unusual things like the De Lisle silenced carbine, which I was able to see for myself on a visit to the latter in Leeds (well worth it!). And understanding the capabilities, limitations and availability of that weapon helped shape the story itself. So, not a gripe. Just a bit of well-meant advice, from someone who’s learning from his mistakes. Double-check the stuff you kind-of-know you’re not too sure of. And please let me know what things I'm still getting embarrassingly wrong, won't you? And in the meantime… Oi, Yanks! Hands off our Sten guns! (Seriously, I now know they’re horrible to hold!) P.S. – I’ve just realised that much of the above may be largely irrelevant if you’re a gamer, playing those games. But I don’t. My namesake Trevor is quite enough for me! And seriously, I know full well that neither YouTube, gaming – nor escapist action thrillers – can give you an accurate impression of what it's like to use one of these weapons in the flesh or, God forbid, to have it used on you. But that doesn't mean that as creators we shouldn't try to get closer, does it? THE BORODINO SACRIFICE, the first book in my CHASING MERCURY series, is now available on Amazon here. Here I go again, thinking with my pen – finding out what I think about something by writing about it. (It’s almost as though writing were an intellectual, exploratory, ambitious endeavour and not an action that can be reduced to its component parts and imitated by a machine…) Anyway, cut to the chase… In fact, cut to Chasing Mercury, my series of what looks like being three espionage/action adventure thrillers set in the immediate postwar period. I’ve touched on this before, when I talked about some historical authors seemingly fighting the urge to give their characters cellphones in my piece about world-building and wordcounts. But there I was discussing different stylistic conventions of historical novels, from the modern-day framing narrative to the ‘plunge right in and make it feel immediate’ lobby... Here I’m thinking about honesty (and how to fake it, as Groucho Marx, Sam Goldwyn, George Burns, Jean Giraudoux or ChatGPT might have said). And specifically, honesty in representing the way people thought and felt during the period. Not necessarily how they expressed these thoughts and feelings, because representing period dialogue must always be a balancing act and a stylistic choice, especially the further back in history you go. But being true to the kind of underlying mindset and reactions that your characters would have; that goes to the heart of motivation, plot and everything. And of course it’s still a balancing act. No one wants to read a hero who’s loaded with all the prejudices of his age. Nor, I think, should we be happy with one who is so anachronistically ‘woke’ that he or she (or they) has none at all. Or not in a genre novel, anyway, even if you’re playing with that genre in other ways. But let’s get specific and look at my period, WWII or just after. In recent years there has been a very dishonest propaganda campaign waged to misrepresent the national mood during the war – and thereby to undermine the narrative of its aftermath. Yes, I’m talking about that bloody poster. I know the bookshop it was miraculously rediscovered in. (You would be hard pressed to find so many pairs of green wellies in any other secondhand bookshop!) And I also know the inconvenient truth about KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON – that it wasn’t used, because when this poster campaign was tested on the public, the establishment was told in no uncertain terms to come back with something less patrician and more inclusive. And they did, adopting a new tone of mutual respect and responsibility that would contribute, when the fighting was over, to the shift in the notion of national duty and, ultimately, to the introduction of the welfare state and the NHS. And if you don’t believe that the efforts to popularise this poster were a desperate propaganda campaign – to bend national positivity-in-the-face-of-adversity to sinister, retrograde ends – look at what was going on at the same time. Look at the 2012 London Olympics. Remember how great most people thought the opening ceremony was, despite all our gloomy predictions. And remember those few, bitter voices raised in dissent: the unreconstructed Tories whinging about multicultural claptrap. What they hated, as in 1945, was the emergence of a new kind of national pride, one open and optimistic and far removed from the narrow, outdated narrative they thought they owned. In that moment they sensed their own irrelevance (even the Queen and James Bond were against them!). And so, yes, spoilt brats that they are, they decided to smash everything up. And the rest is indeed history. And tragedy. But my point here is how insidious the misrepresentation of the way people actually thought and felt can be. And if you want another example, look at the (to me, genuinely) astonishing success of the latest All Quiet on the Western Front movie, which not only plays fast and loose with the history and the source material, but also reanimates the same betrayal narrative advanced by the Nazis. Apart from the Germans, who think about these things, no one else seems to have noticed. But back to the Chasing Mercury books. No, I don’t want to lazily write my 1945-48 characters as though they somehow have access to 24-hour rolling news and decades of perspective. Nor do I want them to feel like ghosts (using the terms of that previous blog post, these are ‘plunge right in’ stories, not framed historical pieces). And so I have to juggle, of course. Whilst walking a tightrope. Over a minefield (where the Allies are using POWs to clear the mines and redesignating them Surrendered Enemy Personnel to get around the Geneva Convention). And I think what it comes down to is honesty of intentions. So here, a bit like an accidental or impromptu manifesto, are mine: To weave my fiction into the historical events in such a way that the reader is neither misled into thinking that the fictionalised events are factually true nor insulted by obviously inauthentic representations of the period. To do this by drawing on a variety of research, where possible some of it original, rather than serving up the same old detail from the same old history book that every other author refers to. To limit the extent to which this context is ‘info-dumped’ on the reader – and ideally to achieve this by limiting the knowledge and understanding of each character to what they would actually know and understand at the time. To do all this without losing their relevance and appeal to a present day audience. KEEP FAITHFUL & STAY FRESH! The Borodino Sacrifice, Book One in the Chasing Mercury series, is on sale now. Book Two will be released on 31 August 2024. It started so hopefully. Carefully researched, carefully targeted approaches to carefully selected agents – literally just a handful of the ones I really thought… really wanted… Yeah, right. After the seventh form rejection, with no full requests, I had to consider two alternative but equally plausible explanations. One, they were reading the letter and sample chapters and were so uninspired they didn’t think I warranted a personalised reply, let alone a request for more. Two, they weren’t reading them, not properly, or not at all. I may be an insecure writer but I am not ready to accept option one. So then I saw invitations on social media for authors to submit directly to this new (to me) kind of publisher: digital first. The reasoning here being that since they don’t do print editions, or only print-on-demand, or only after the success of the eBook, they can afford to publish many more titles than trad publishers/imprints. No advance, but supposedly you get help with the marketing and a decent slice of the profits. I did my due diligence and sorted the rip-off-artists/hybrid publishers from the (reasonably) respectable-looking firms, which in at least two cases were actually divisions/imprints of big trad publishing groups. I looked at what they published, carefully prepared my pitch and sent off my full manuscript with the promise that this time, they WOULD read it. And got pretty-much-form rejections. Now, I realise that my book(s) do not fit snugly into the illustration-of-a-woman-against-a-backdrop-of-two-up-two-down-terraces-with-Spitfires-in-the-sky/illustration-of-a-woman-walking-away-from-us-with-the-White-Cliffs-of-Dover/Auschwitz-in-the-background-(Spitfires-optional) market, but in another way, they kind of could. Enough, as I intimated in my carefully worded query letters, to warrant a discussion about cross-genre marketing possibilities – or at least a considered/considerate reply, you’d think (well, I thought; maybe you’re smarter). And then what I thought was this… Shit. Because I realised that I had painted myself into the proverbial corner. How could I now go back to querying agents, having taken it upon myself to do their job and submit to publishers directly, even if only a couple of the twinsets-and-Spitfires ones? You can’t write to someone and say I think publishers will be excited about this novel series, and by the way I’ve already been rejected by x, y and z. So there you go. I always wondered what would finally make me take the plunge and decide to self-publish. Was it going to be 10 form rejections from literary agents? 20? 50? No. Turns out it was seven and an assumed/probable rejection. Plus two-and-a-probable from digital first publishers. And the strong suspicion that no one was even reading the letters that had taken me hours, sometimes days, to write, let alone the stuff that had taken me years. Which isn’t right, is it? Just like those assumed and probable rejections from the ones who say they’re so busy they can’t guarantee they’ll get back to you at all. Anyway. Looks like the next time I write anything here I'll be complaining about how hard it is to get started in self-publishing. Help! (But not like that – you’re not getting my money as well as all the years of effort. It's time for a bit of DIY.) I've thought about 1976 a fair bit over the last few years. You might remember I wrote a novella and mentioned it here. (And in this post about log lines, where I even shared a mocked-up cover.) I've come to realise that it was a formative year for me. Hardly surprising. I was 11, tentatively dipping a little pink toe into the encroaching tides of puberty and adulthood. How? Well, here's an example. My father actually used to come home from London more often than he does in 76. Like any other commuter (although of course he was anything but) he would bring with him his half-read Evening Standard. And I, starved of what I never even imagined would one day be termed 'content', would pore over it that night or next morning. Despite the massively different media environment, I don't think kids have changed that much. At 11, I instinctively avoided current affairs, as well as most of the sport my father was interested in. Star Wars may have been shooting nearby but it was still far, far away for all of us and 'Cod Wars!' didn't have quite the same ring to it. Everything else seemed to be to do with the IRA, which even the adults didn't understand. So instead, and with that little pink puberty-toe (!) tingling, I flicked through the fingertip-smudging newsprint in search of fresh imagery. Cinema ads! Tiny photographs in magic-eye halftones with mystical titles bespeaking a higher level of adult understanding that was to prove illusory. The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea. What even was that? An Oedipal-Nietzschean drama set in the world of merchant shipping, starring Kris Kristofferson and adapted from the novel by Yukio Mishima. I'd love to see an elevator pitch for that now, in these days of Chris Hemsworth in tactical gear on Netflix... Then (because we're coming to it), a page or two later and probably after dipping into the completely unintelligible horoscopes in search of pre-toe-tingling promises of true romance, the comic strips. (I told you we were coming to it!) MODESTY BLAISE by Peter O'Donnell, illustrated by Romero. Black and white. Three frames a day, no more. None of the subtlety and charm that I was to discover had predated Romero in the original art of Jim Holdaway. But I was hooked. The daily strips were painfully brief but the stories were long-form, often lasting several months, with complex plots and great scrapes. The set piece captures and escapes were thoughtfully put together. Most of all, the characters were compelling and the relationship between Modesty and her sidekick Willie Garvin completely unique and intriguing. Soon I was clipping out the strips and collecting them as graphic novels in mismatched binders. In time, O'Donnell's actual Modesty Blaise novels would follow. And although their quality would fall off somewhat as I brought myself up to date with the classics from the 60s and began waiting for new releases in the 80s, these more sophisticated and substantial versions of the stories – and their influence, which is what this is about – would stay with me all my life. Was it just me? I was able to pick up those earlier titles because every secondhand bookstall was full of them back then, usually with embarrassingly unrepresentative sexploitation covers courtesy of the unscrupulous Pan Books. But then there were the quotes from the superfans, of course. Like Kingsley Amis calling Modesty and Willie "one of the great partnerships in fiction, bearing comparisons with that of Holmes and Watson". Quentin Tarantino would later join in too and in fact you see O'Donnell's peril/resolution set pieces influencing thriller writers and filmmakers up to the present day, more often than not unacknowledged. Much more importantly, there were girls who liked Modesty and who saw her as a progenitor for female characters from Buffy to Lisbeth Salander, not just as a bit of ill-cast cleavage on a Pan cover. Yes, she was written by a male author, but somehow (even if in other respects Modesty is admittedly a product of her time) he had gone far beyond the Male Gaze and won plaudits for it. Anyway, it was a female-male partnership he was writing, so there was justification aplenty. So there you are. The seeds were sown. One day, I would create a series of action adventures that would be inspired by (or reflect, or reimagine...) the Modesty Blaise comic strips and novels. And because I first came to them not as contemporary thrillers but as period pieces (the mid 60s is literally a lifetime away when you're an 11-year-old in 1976), I would set them in a historical context. Which would let me throw in other influences from my content consumption as a young man, from Bond and Le Carré to Where Eagles Dare. That's how the Chasing Mercury series was born. I thought it might be useful to describe it in terms of its inspirations rather than purely as a reaction to a perceived market opportunity – as I began to do when I asked recently Why are my novel's influences not the same as its comps? And I wrote this follow-up post, too, because I have been thinking about how to address the issue of comparison titles for a blurb, if I decide to self-publish – and because I have to say something that means something to me as well as to the Amazon algorithms... So thank you for bearing with me, if you have. Now you know where it all started. |

My story...I've been writing for as long as I can remember (I think my first letter was a P). I got a degree writing about other people's writing and ever since then I've earned a living writing commercially, one way or another. But I never stopped writing and refining my own stuff. I just didn't do anything with it, until now. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed